Types of Verbs in Te Reo Māori

In the te reo Māori class I attend we’ve been covering different types of verbs and how they affect sentence construction. This post is a tidied up version of my notes.

In the te reo Māori class I attend we’ve been covering different types of verbs and how they affect sentence construction. This post is a tidied up version of my notes.

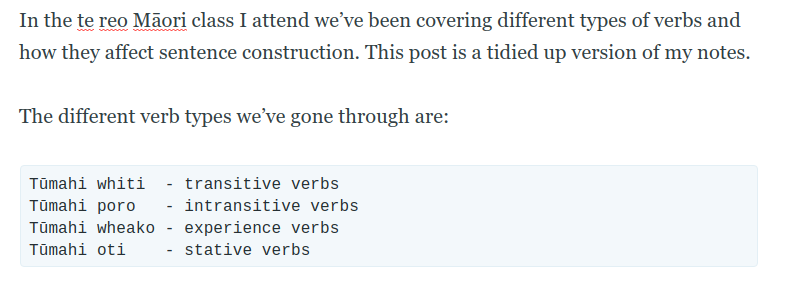

The different verb types we’ve gone through are:

Tūmahi whiti - transitive verbs

Tūmahi poro - intransitive verbs

Tūmahi wheako - experience verbs

Tūmahi oti - stative verbsBefore going through verbs, a brief diversion into “reremahi” - action sentences.

Reremahi

Reremahi, or action sentences, are sentences where the main focus is the action being performed. They involve a subject performing an action and optionally an object that the action is performed upon.

These types of sentence structures follow the form:

<Tense marker> + <verb> + <subject>

<Tense marker> + <verb> + <subject> + <particle i/ki> + <object>The tense marker indicates the time that the action is performed - past, present or future. Common tense markers are:

| Tense Marker | Meaning | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kei te | present tense, continuous action | Kei te oma au | I am running |

| E ... ana | present tense, continuous action | E oma ana au | I am running |

| Ka | future tense | Ka oma au | I will run |

| I | past tense | I oma au | I ran |

| I te | past tense, continuous action | I te oma au | I was running |

| Kua | past perfect tense* | Kua oma au | I have run |

*An action in the past in relation to something even further back in the past, sometimes described as “recent past tense”. It is translated as “have” in English.

A simple sentence example would be:

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| I am eating | Kei te kai au |

| Tense marker | Kei te (present tense, continuous) |

| Verb | kai (eat) |

| Subject | au (me/I) |

An example that uses an object:

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| He/She has eaten the apple | Kua kai ia i te āporo |

| Tense marker | kua (past perfect tense) |

| Verb | kai (eat) |

| Subject | ia (he/she) |

| Particle | i (object marker) |

| Object | te āporo (the apple) |

Tūmahi

“Tūmahi” is the te reo Māori word for ‘verb’. Verbs are action or doing words. If someone or something is doing something or performing an action, then that action is the verb. “Mahi” in te reo Māori can mean “to do” which helps to remember “tūmahi” as a doing word.

There are different types of verbs and I’ll describe these in the following sections. Why do we need to be able to identify the types of verbs? One common difficulty in constructing te reo Māori sentences is knowing whether to use “i” or “ki” to mark the object of the sentence. Different verb types use either “i” or “ki”. By being able to identify the type of verb it tells us which object marker to use.

Tūmahi Whiti

Tūmahi whiti are transitive verbs. A transitive verb expresses an action that affects an object. If it doesn’t affect an object it’s not a transitive verb.

For example, the verb “to hit” - saying “I hit” doesn’t make much sense - the sentence needs an object to complete the thought. “I hit the ball” - here “hit” is a transitive verb with “the ball” being the object.

Another example is the verb “to carry”. “The boy carried” isn’t a complete sentence, it needs an object. “carry” is therefore a transitive verb. “The boy carried the box”.

Why do we need to know if a verb is transitive or not? In English there is no object marker in a sentence - the object follows the verb. But in te reo Māori, objects are marked with a particle - either “i” or “ki”. Transitive verbs in te reo Māori use the particle “i” to mark the object. The previous example in te reo Māori would be:

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| I hit the ball | I patu au i te pōro |

| Tense marker | I (past tense) |

| Verb | patu (strike, hit) |

| Subject | au (me/I) |

| Object marker particle | i (because patu is a transitive verb) |

| Object | te pōro (the ball) |

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| The boy carried the box | I kawe te tama i te pouaka |

| Tense marker | I (past tense) |

| Verb | kawe (carry) |

| Subject | te tama (the boy) |

| Object marker particle | i (because kawe is a transitive verb) |

| Object | te pouaka (the box) |

Tūmahi poro

Tūmahi poro are intransitive verbs. These are verbs that don’t affect an object. They are just actions that subjects do that affect themselves. For example, the verb “to arrive”. A person can arrive, but they can’t arrive something. These sentences in te reo Māori don’t have an object at all:

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| They are arriving | Kei te tae rātou |

| Tense marker | Kei te (present tense) |

| Verb | tae (arrive) |

| Subject | rātou (them, three or more) |

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| The cat has sat | Kua noho te ngeru |

| Tense marker | kua (past perfect tense) |

| Verb | noho (sit) |

| Subject | te ngeru (the cat) |

Note that extra information can be added to a sentence - “the cat has sat on the mat” for example. But because “sat” is intransitive it has no object - the “on the mat” part of the sentence is not the object of the sentence, it’s extra information providing the location where the action occurred.

Tūmahi Wheako

Tūmahi wheako are experience verbs. These are verbs whereby the subject is an experiencer of something. They name a mental state or perception that the subject perceives. In these words the object of the sentence is the source of the experience.

Because they have an object they are similar to tūmahi whiti, transitive verbs, so why do we distinguish between them in te reo Māori? We do this because sentences with experience verbs mark the object (or the source of the experience) using the particle “ki” rather than the particle “i” which transitive verbs use.

Knowing which verbs are experience verbs requires memorising them. These are some of the experience verbs we’ve covered in class:

| Experience Verb | Meaning |

|---|---|

| pīrangi | hope/desire |

| whakaaro | thought/idea |

| hiahia | want/need |

| moemoeā | dream |

| aroha | love |

| mōhio | know |

| mahara | think about/consider |

| āwangawanga | anxious |

Some example sentences:

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| I love you | Kei te aroha au ki a koe |

| Tense marker | kei te (present tense) |

| Verb | aroha (love) |

| Subject | au (me/I) |

| Object marker particle | ki (because aroha is an experience verb) |

| Object | a koe (you - the ‘a’ is a particle used in places to identify a pronoun/name) |

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| I dreamt about my car | I moemoeā au ki tōku motoka |

| Tense marker | I (past tense) |

| Verb | moemoeā (dream) |

| Subject | au (me/I) |

| Object marker particle | ki (because moemoeā is an experience verb) |

| Object | tōku motoka (my car) |

There are some exceptions to remember. The following are classified as experience verbs but they use “i” as the object marker:

- kite

- rongo

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| We will see the moon | Ka kite tātou i te marama |

| Tense marker | Ka (future tense) |

| Verb | kite (see) |

| Subject | tātou (we, three or more) |

| Object marker particle | i (because kite is an exception to the experience verb rule) |

| Object | te marama (the moon) |

I don’t know why these are exceptions. Using the correct object marker for experience verbs seems to be a matter of remembering which verbs are experience verbs and remembering which are the exceptions within that list.

Tūmahi oti

Tūmahi oti are stative verbs. They’re also known as Tūāhua oti. A stative verb refers to a state or change of state rather than an action and the way the sentence is structured is quite different.

There’s no rule to identify whether a verb is a stative verb - they have to be remembered, much like tūmahi wheako. Some examples we learnt in class:

| Stative | Meaning |

|---|---|

| pau | consumed |

| mau | firm/secure |

| riro | taken |

| pakaru | broken |

| oti | completed |

| motu | be cut / severed |

| mahue | deserted |

| mākona | satisfied |

| taka | fall |

| mate | dead |

| ea | fulfilled |

| ora | life |

| tutuki | completed |

| ngaro | lost |

The sentence structure for sentences with tūmahi oti is different to that of sentences with the other types of verb. In these sentences the object of the sentence does not have an object marker particle, instead the subject of the sentence has one. They are structured like this:

<Tense marker> + <stative verb> + <object>

<Tense marker> + <stative verb> + <object> + <particle i> + <subject>A example of the first form:

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| The window was broken | I pakaru te matapihi |

| Tense marker | I (past tense) |

| Verb | pakaru (broken) |

| Object | te matapihi (the window) |

Notice the difference between the other verbs. The window is not breaking something. The window is in the state of broken. The agent is marked with “i” if there is one:

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| The window was broken by the girl | I pakaru te matapihi i te kōtiro |

| Tense marker | I (past tense) |

| Verb | pakaru (broken) |

| Object | te matapihi (the window) |

| Subject marker particle | i (because pakaru is a stative verb) |

| Subject | te kōtiro (the girl) |

In sentences with stative verbs the “i” can be read as “by the” - the state of the object of the sentence has been reached by the actions of the subject.

| English | Māori |

|---|---|

| He has been left behind by the bus | Kua mahue ia i te pahi |

| Tense marker | kua (past perfect tense) |

| Verb | mahue (abandoned, left behind) |

| Object | ia (he) |

| Subject marker particle | i (because mahue is a stative verb) |

| Subject | te pahi (the bus) |

The above example would probably read in English as “he missed the bus”, but because the verb used for “missed” is the stative verb “mahue”, a literal reading is “he has been left behind by the bus”. “He” is the object that is in the state of having been left behind by the actions of the subject, the bus.

Reading sentences with stative verbs is similar to reading passive sentences - which I'll cover in a later post. It’s easy to get the subject and object mixed up, but memorising the common stative verbs and learning to recognise when they appear in a sentence will help.